Pulp – Different Class

The year is 1995 and the battle of the bands is being hyped to death. In the Manchester corner, Oasis have released the uninspiring “Roll With It” off the most overrated album of all time; in the Colchester corner Blur have put out the jaunty “Country House” from their uneven critique of Middle England, “The Great Escape”.

But there are four corners to this ring. Radiohead are crouching down with “The Bends” in the Oxford corner, gearing up to release their full potential. In the Sheffield one, Pulp are already on top of their game, head and shoulders above the rest, and they’re seething with a focused, stunningly articulate, burning rage. Much as I like Radiohead’s second album, “Different Class” is, well, different class.

And what an album name that is! Although my parents were both from middle/working-class families, my own upbringing was decidedly middle-class. To a 13-year old living in a “no sex please, we’re British” well-to-do village, this album was a seismic shock to the system. To be honest, even if I thought I could, I couldn’t begin to understand half of it. For me, parks were somewhere you walked, birds were something that woke you up in the morning, and grass was something you played cricket on. As for “A Year in Provence”, my dad was reading it when I got the album, and here Jarvis was, telling him to shove it up his a….

“I Spy” ripped the wool off my decidedly bourgeois eyes. In this alternative universe, “parks are car parks, grass is something you smoke, and birds are something you shag”.

The insanely strong first seven songs of the album flit between light and dark, the overt and the covert, romance and seediness, hope and despair. The musically upbeat opener, “Mis-shapes”, draws the battle lines for the coming class war, telling us “you could end up with a smack in the mouth just for standing out”, a sentiment that sounds like it could be straight out of the “Black Lives Matter” movement of today.

And so it continues: “We’re making a move, we’re making it now, we’re coming out of the sidelines.” / “We want your homes, we want your lives, we want the things you won’t allow us. We won’t use guns, we won’t use bombs, we’ll use the one thing we’ve got more of; that’s our minds.”

Although the next verse was also intended to describe the class divide, it accidentally also foresees the whole millennial/boomer clash: “We learnt too much at school. Now we can’t help but see that the future that you’ve got marked out is nothing much to shout about”. That’s an awful lot of prescience packed into the very first track.

It wouldn’t be a Jarvis Cocker-penned album without a lot of material about sex, and this would get far darker on Pulp’s follow-up album, “This is Hardcore”. Tracks 2, 4 and 6 are all awash with it, with the first of the “dark side” tracks particularly nasty in a hollow, desperate way.

“Pencil Skirt” deals with infidelity that’s begun before marriage and seems likely to continue after. He’s not meeting the bride-to-be out of any lofty ideals as he confesses in the outro: “I only come here, ‘cos I know it makes you sad. I only do it, ‘cos I know you know it’s bad. It’s ugly and it shouldn’t be like that, but it’s turning me on.” The creeping, backing music plays on as he watches his conscience disappear.

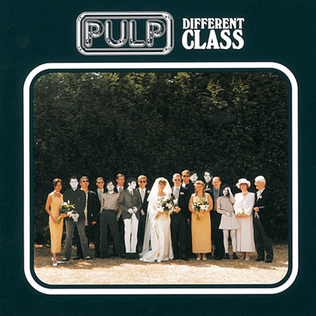

“I Spy” uses a James Bond style backing track as Jarvis pits himself against an adversary that seems to be the entire upper middle class/aristocracy. Just as the band sneak into a wedding photo on the album cover, he surreptitiously wreaks havoc on a couple, smoking the man’s cigars, drinking his brandy and messing up the bed he and his wife chose together. There’s no denying his jealousy either; “you never let your mask slip, you’re never hurried” takes aim at that unshakeable and unmistakeable confidence that those born into old money possess.

“Live Bed Show” is a wistful take on an ended relationship from a bed’s point of view. There’s some nice meta work with the snare echoing the “headboard banging in the night” and a lush, dreamy keyboard chord that is only used once to back “everything was going right”. But we’ll move on as “if this show was televised, no-one would watch it, not tonight, but seven years ago…”

I’ve got through ten or so paragraphs and not even mentioned “Common People”? Blasphemy! Despite the song maintaining a relatively sparse sound in places, all 48 tracks were used in recording it, and apparently it wasn’t until Jarvis added an acoustic guitar that it all came together. The result is a piece that doesn’t sound like any other song. It doesn’t even sound like any of the others on the album.

As per usual, Jarvis is the protagonist in the song and after a girl. This time, she’s a kind of “poverty tourist” from Greece who’s a few classes above him. That doesn’t bother him too much though, as she’s buying the rum and cola and wants to sleep with “common people” like him.

The way he turns that line back on her with “You want to see what common people see. You want to sleep with common people. You want to sleep with common people like me?” within the context of a song is utter genius.

After beginning the “poverty tour” inauspiciously at a supermarket, Jarvis lets the Greek art student have it in one grandiose as hell rant/chorus that lasts a magnificent 3 minutes, explaining how she’ll never understand what it means to be poor as at any time she can call her dad and he’ll stop it all, “and the chip-stains and grease will come out in the bath”. Excoriating.

“Common People” has a great retro video showcasing Jarvis’ unique dance moves, as does “Disco 2000”, the other massive, gloriously poppy single from the album. Naturally, Jarvis is after another lady. This one’s not from a different class, but she does seem to be in a different league.

At school, Deborah let him walk her to her “very small house with woodchip on the wall”. but it meant nothing to her. She wasn’t buying the written-in-the-stars being “born within an hour of each other” claptrap that Jarvis is. Still, he keeps on hoping, thinking things will be different when they’re all fully-grown in the year 2000. Fast-forward to the future and Jarvis is “damp and lonely” (lovely image) and Deborah’s got a kid, but he still wants to meet up…and the song remains relentlessly upbeat.

“Something Changed” kicks off the second half of the album. It’s a far more standard love song, so of course it was the one I really liked when I first got the album. The fact that everything that is described within the song didn’t actually happen is also a nice, if somewhat English GCSE creative writing essay style twist. In case you’re wondering what I’m talking about, he wrote the song “two hours before they met” i.e. they didn’t meet.

Track 8 is “Sorted for E’s and Wizz”, which caused a furore with the same tabloid reading idiots who thought Pulp Fiction was a pro drugs film. I particularly like the way the song beats back into life after “you come down” the first couple of times but doesn’t the last, which ends in a possible overdose. “What if you never come down?”

Unfortunately, Jarvis leaves an important part of his brain “somewhere in a field in Hampshire” and I don’t feel like he gets it back until the album closer, “Bar Italia”.

“F.E.E.L.I.N.G.C.A.L.L.E.D.L.O.V.E.” (what is going on with those full stops) resonated with teenage me, but seems obvious and unnecessary now, “Underwear” is less erudite than the earlier “sex songs”, and “Monday Morning” is a daily grind number about a city alcoholic that lacks the gleam of the earlier gems.

Best to head straight to the “Bar Italia” flute intro then. This is hands-down the best song I know describing the dizzy, semi-comatose state of the end of a night/early morning. “If they knocked down this place, this place would still look much better than you” is a wonderfully unflattering line and “What did you lose? It’s OK, it’s just your mind” sums up the whole ridiculousness and futility of going out, destroying yourself and reaching the state where the potential loss of a wallet/phone is far more important than the damage you’re doing to your brain.

Twenty-five years have passed since “Different Class” was released, and it’s aged extremely well while remaining very much a snapshot of the time it was written. It’s also interesting to note that the class war idea touted in the opening track recurs throughout the first four songs, but is then more or less forgotten about in a haze of drink, drugs and sex. Let’s hope the movements for change of today don’t run out of steam in the same way.